This story is also available for download from major ebook retailers.

Inspector Wilde was in a fine mood when he arrived at the headquarters of Salmagundi’s Legion of Peace, carrying three paper-wrapped sandwiches and an armload of printed broadsheets. He had a spring in his step and walked in time to one of the latest music hall ditties, which he whistled cheerfully for the benefit of his coworkers. All along the gaslit passage, clerks and secretaries poked their heads out of their rooms and stared, in wonder and admiration at his audacity. Most of them smiled as he passed, and a few of the braver ones tapped their feet along with the tune for a few moments before dashing back to their desks to avoid the ire of their supervisors. Wilde laughed as he passed a room full of secretaries who somehow managed to type in time with the music.

Midway down the hallway was the Chief Inspector’s office, which was fronted by a small antechamber in which her secretary, Marguerite, was busy making sense of several unsightly piles of documents. Her work table was a model of efficiency. Her pens and pencils were all neatly arranged to one side, along with writing paper and a three-section typewriter for preparing documents in triplicate. A rack of empty pneumatic capsules waited nearby to be filled and dispatched.

Marguerite smiled as Wilde approached, delighted by the cheerful whistling. Wilde leaned down, eyebrows arched, and tossed Marguerite the top sandwich in his stack.

“And a girl in uniform’s just the thing for me…” Wilde said playfully, completing the refrain of the tune in Marguerite’s ear.

“Max!” Marguerite exclaimed, her cheeks flushing. She pushed him away and made a show of reorganizing the papers on her desk. “You mustn’t say things like that to me. People will talk.”

“Well, if ‘people’ are going to talk, don’t you think we should give them something to talk about?” Wilde asked, flashing one of his trademark recruitment smiles.

Marguerite was trying to come up with a reply when a third voice interrupted. “Max, get in here!”

Marguerite jumped in shock and pulled a handful of papers between herself and Wilde, as if to deny that they had even been speaking. Wilde was also caught by surprise, but retained his composure. He looked over at the polished voicepipe mounted next to Marguerite’s table just in time to hear the Chief Inspector’s voice again.

“Now!”

* * *

Wilde kept his head high as he sauntered across Chief Inspector Cerys’s cluttered office. Behind him, a sheepish Marguerite closed the door as quietly as she could. What might normally have been a sizable, bland, and dutifully bureaucratic office had, since the Chief Inspector moved in, been transformed into a nest of filing cabinets, pigeonhole shelves, and chairs covered in files and loose papers.

The room was lit entirely by gas lamps, for both of its windows had been tightly shuttered. Located on the top layer of Salmagundi, Legion Headquarters was gifted and cursed with an overwhelming view of the vast horizonless sky that surrounded the city. The silver-gray expanse of ether was a sight of unparalleled majesty and terror. Though sky-borne steamships traveled freely from one floating city to another, urban dwellers could not help but fear the mysterious beasts and horrors that lurked in the great beyond, thanks to old sailors’ stories of unfathomable monstrosities. However, even fear could not defeat the human drive for commerce. For every cargo ship lost to the ether, five more were already being built in Salmagundi’s shipyards, like heads of a great industrial hydra.

The largest piece of furniture in the Chief Inspector’s office was her massive Legion-issue desk, which was covered in papers, pens, and miscellanea. However, it was a metal coffee percolator resting on a stand nearby that was the true focal point of the room. A set of insulated pipes extended from the wall and into the percolator’s base, keeping the coffee hot by pumping steam through it from the building’s main line.

Chief Inspector Cerys looked up from a collection of reports, coffee cup in hand, and gave Wilde a look. “Max, I’ll thank you to stop flirting with my secretary all the bloody time.”

“Why, Chief?” Wilde asked, setting one of the sandwiches down by Cerys and then pulling over a chair. “If you ask me, I think she rather likes it.”

Cerys gave him another look as she began to unwrap her meal. “She does, Max. She likes it too much.” Cerys waved a typewritten form in front of Wilde’s face. The document was so complex as to be less legible than a massive ink spot, but it would drive some anonymous bureaucrat into a frenzy if even a single T was left uncrossed before filing. “Marguerite’s the only person in this blasted place who can read these damn things, and she’s useless for half an hour after you bat your pretty little eyes at her.”

“‘Pretty little eyes,’ Chief?” Wilde asked. “Why, I didn’t know you cared.”

“Shut up, Max.”

“Yes, Chief.”

Cerys bit into her sandwich and let out a sigh; Wilde suspected it was her first real meal of the day. “Mmmm! Herr Grosse comes through again.”

“I’m sure he’ll be happy to hear it,” Wilde replied. “What’s on the agenda for today?”

“We’re unusually light on terrorist attacks and serial murderers at the moment, so we’re ‘lending a hand’ with Surveillance.”

“Espionage and tailing suspects?” Wilde asked hopefully.

“Examining subversive propaganda for clues,” Cerys replied.

Wilde made a face at the thought of such a boring activity. “Just so we’re clear, I’m not on duty for another five minutes.”

“You’re not on duty until I finish my sandwich,” Cerys countered.

“Deal.”

Leaning back in his chair, Wilde began to read one of the broadsheets he had brought with him. Within a minute, he was all but giggling like a schoolboy.

“What’re you so happy about?” Cerys asked, between mouthfuls of sandwich and mayonnaise.

Wilde quickly cleared his throat. “Er…. Nothing, Chief.” His eyes involuntarily read the next line of text and another fit of laughter took him.

“Nothing?”

“Eh…heh…. Um, yes, nothing.” Wilde held up the broadsheet for Cerys’s inspection. “It’s just Mr. Salad Monday. He’s giving Deacon Fortesque a roasting over his latest political tract.”

“What?” Cerys demanded, bewildered.

“Here, here, listen to this. He writes, quote, ‘While I suspect that the Hon. DeacFort is sincere in his belief that the threat of terrorism can be removed by simply shooting every suspected saboteur or socialist, plus one in ten persons of an inferior income distribution, he has forgotten two significant points. First, that the same result could be achieved more rapidly, cheaply, and without a reduction of the work force by improving working conditions and raising lower-income pay rates; and second, that he is an unmitigated fool whose longevity in the printed world can only be ascribed to his wealth, influence, and the public demand for entertaining fiction to read after breakfast,’ unquote!” Wilde lowered the broadsheet, the grin on his face outstripping most industrial bridges. “Isn’t that terrific?”

Cerys blinked several times. “Max, what in Heaven’s name is wrong with you?”

“You don’t think it’s funny?”

“I think it’s a waste of print, and I’m surprised you don’t agree. Besides, we’ve got more important things to do.” She tossed him a folder of documents. “Here, make yourself useful and read this.”

Wilde set the broadsheets aside and thumbed through the folder. It contained a number of obscure pamphlets and political chapbooks, all machine-printed on cheap paper. They had been bound with red ribbon, and each was plastered with a paper tab bearing the ominous statement “Forbidden!” As he opened one and began to skim the text, Wilde felt a nagging sense that he had read the author’s work somewhere before. After a moment, the recollection came to him and he burst out laughing.

“What?” Cerys demanded, from behind her cup of coffee.

Struggling to keep his laughter under control, Wilde pointed to one of the chapbooks. “This is by Fredrick William Slater, isn’t it?”

Cerys almost dropped her coffee. “How did you…?”

Wilde held the chapbook a little higher, and pointed to it emphatically. “Isn’t it?”

“Slater’s name isn’t on any of those books. How’d you know it was him?” Cerys went to take another sip of coffee, and then pointed the cup at Wilde menacingly. “And don’t tell me it was a lucky guess. No one in the Legion just pulls the name Professor F. W. Slater out of their hat.”

“I recognized the writing style, Chief,” Wilde answered. “The guy’s got a pretty distinct voice, you know.”

“You don’t strike me as the kind of person who makes a habit of reading essays on social philosophy, Max. Mind explaining this happy coincidence to me? Or do I have to get the bucket of water?”

Wilde gave an expression of jovial terror. “Not Old Truth Maker! Anything but Old—“

“Shut up, Max, and answer my question.”

“Alright, alright. He writes for the papers, so I read him just about every morning.”

“The papers?” Cerys asked. “He’s not a reporter.”

“No, no, not the newspapers. The broadsheets.” Wilde held up one of the oversized printed sheets he had brought in with him. It resembled a conventional newspaper, but the upper half of the page was given over to large editorials, while the lower half was divided into columns of small-print articles; in many cases, the smaller segments were only a few lines long. “Tit-tat.”

“Tit-tat?” Cerys asked, bewildered.

“Right. Tit-tat. Slater’s a tatter.” Wilde was clearly under the mistaken impression that they were coming to some sort of mutual comprehension.

“What’s a ‘tatter’?”

There was a lengthy pause, as Wilde realized his superior was confused, but not how to help. Somewhat hesitantly, he ventured, “A tatter is…someone who does tit-tat.”

Cerys lowered her face into her hands. She had a deep-seated urge to shoot him. “Max…what does ‘tit-tat’ mean?”

“Oh!” Wilde exclaimed. He held up the broadsheet again. “It’s…um…. Well, it’s tit-tat.” When this answer made Cerys rise half out of her chair with murder in her eyes, Wilde quickly added, “Wait! Wait! It’s like a conversation in print!”

“What?”

“Well, the bigwigs, like Professor Slater, publish their opinions on topics of the day. Then they all read each other’s essays and mail in replies, and then those get printed…and so on.”

Cerys paused on the verge of a rant against modern society and how it was conspiring to annoy her. “You know,” she said, clearly surprised, “that almost makes sense, in a mind-numbing kind of way.” She stepped around the desk and snatched the broadsheet out of Wilde’s hands, pointing at the maze of print. “But then, what’s all this here? Don’t tell me ‘Mr. Jervais Mutton’ is the name of some brilliant philosopher, Max.”

Wilde laughed. “Oh, no, no. Those are all tatters. They’re ordinary people who send in their own comments. Most of them never see print, but the really juicy ones get tossed in along with the ‘professional’ stuff because it’s fun to read.”

“Fun to read?”

“Audience loves ’em,” Wilde confirmed with a nod. “Ask me, they’re more popular than the articles they’re responding to. People have whole conversations in print, arguing back and forth.”

“Conversations? How frequently are these released?”

“Well….” Wilde sat back in his chair and considered the question. “The more respectable printers only do one issue a day, but they tend to be a bit light on the commentary anyway. Most places have a morning and an evening edition, so you can read a comment and a response in one day if you’re lucky.” He leaned forward again, clearly excited at the prospect of explaining something to Cerys. “But the really good ones…the houses that print the really juicy arguments…they sometimes get in as many as three or four a day. Plenty of tit-tat there.”

Cerys stared at him, her mouth struggling to form a response. “How?” she finally demanded. “How can they print that much in one day?”

“Well, there’s the morning edition that people read during breakfast. Then there’s the afternoon edition, which arrives in time for lunch. And finally there’s an evening edition that shows up in time for dinner. Sometimes they even do a late night printing that shows up sometime in the small hours.”

“Four editions! I’d barely have five minutes to spend reading one. Who has time to read all that, let alone mail in a comment?”

“Clerks, mostly,” Wilde replied. “Typists and secretaries who have to sit at their desks doing nothing while they wait for assignments to show up. And the idle rich, of course. People who think that having too much time on their hands qualifies them to comment on topics they know nothing about.”

Cerys was quiet for a long moment. “Almost reminds me of the government.” She stared at the broadsheet and shook her head. “How long do these arguments last?”

“Days,” Wilde answered. “Weeks sometimes, if they get really heated. So long as the papers sell, the presses keep printing them.”

“How do they keep track of the arguments?”

Wilde pointed to one of the boxes of print. “There’s a little code number in the corner. It tells you which topic the reply goes with, and where it goes in the sequence.”

Cerys was rubbing her forehead with her hand again. “Max, I’m afraid to ask, but why are there strings of letters just sitting in the middle of some of these sentences?”

“What?” Wilde rose from his chair and leaned across the desk. Cerys pointed to one of the comments, and Wilde burst out laughing. “Oh! They’re just abbreviations, Chief. To save on space. The shorter a comment, the more likely it is to get printed.”

“So ‘IIMOT’ means…?”

“We pronounce that ‘eye-moth.’ It means ‘it is my opinion that.’ People use it when they’re about to say something really snooty talking about a topic they don’t understand. It’s great stuff!”

Cerys gave him a look and shook her head. “I can’t believe you actually waste your time with this nonsense.” She glared at the page again. “What about ‘IHN?’”

“‘In Heaven’s name,’ Chief.”

“Oh, honestly, Max!” Cerys exclaimed. “Don’t these people have anything better to do?”

“Desk jobs, Chief,” Wilde reminded her.

“And they really care about what Jervais Mutton has to say about rising coal prices?”

“Nah, Mutton doesn’t discuss commodities. He’s too busy falling over himself to agree with whatever Deacon Fortesque happens to think. Now, Salad Monday, he’s a fun one. He’ll take on five people at once and bring in arguments most of us forgot about ages ago. Frankly, it’s a privilege to watch him in action. He’s an oddball, that one.”

Cerys had returned to her work, and only half glanced up when she replied, “Oh? Why’s that?”

Wilde took her cue, and went back to skimming through the pile of pamphlets and tracts he had been given. “Oh, he just doesn’t fit into the usual categories. Most of the time you can read someone and say ‘he’s a socialist’ or ‘he’s a conservative’ or ‘he’s a capitalist.’ With Salad Monday, you can’t do that. He’s all over the place with what he’s doing. Sure, he tends to agree with the lefties, but he’ll blast them out of the sky when they’re saying something stupid. I mean, he’s probably as anti-government as the anarchists, but he has a great time pointing out how stupid anarchism is. He’s just…everywhere and nowhere, I guess.”

Something about the statement caught Cerys’s interest. “Really? Well, who is he then?”

“Don’t know, Chief. No one does. He’s been around for ages, since tit-tat started, I think. He was already one of the big names when I got into it a couple years back. There’re plenty of theories out there, but he’s one of the pen names no one’s been able to crack yet. He’s probably one of those university types, though. He’s always quoting from this or that, and he’s got the time to stay up-to-date on whatever’s going on.”

“But no one knows who he is?”

“Well….” Wilde hesitated. “You know, it’s funny you’ve got me reading up on Slater, because the current view is that they might be one and the same.”

There was a look in Cerys’s eyes. “Really? Why?” She slowly rose out of her chair and leaned across the desk at Wilde. “You said yourself that Slater’s got a distinctive voice. Wouldn’t that make it obvious?”

“That’s the thing. Salad Monday’s got about as neutral a voice as possible. It’s almost distinct in how indistinct it is. The theory is that it’s someone like Professor Slater, who’s got a very recognizable style, trying not to give himself away. And out of all the bigwigs Mr. Salad Monday takes on, Slater’s the one who usually ends up coming out looking the best. He’ll point out Slater’s flaws, but he usually ends up defending the Professor’s argument, with a few revisions. It’s almost like they’re working together. The only problem is, a busy university man like Slater wouldn’t have time for it.”

“How do you mean?” Cerys asked.

“Salad Monday’s probably the most prolific tatter ever to tit the tat, if you take my meaning.”

“Barely,” Cerys replied without an ounce of humor. “Continue.”

“He writes so much material I’m starting to wonder if he’s actually one person. It seems like he’s got a witty, well thought-out reply to just about every single topic that ever hits print, and he gets them to the printers on the same day, sometimes even by the next issue. And I’ll tell you, Chief, I don’t care how much free time someone has, there’s only so much typing one person can do.”

Cerys was scribbling notes. “Do you think it might be a group of Slater’s students trying to help give his arguments more authority?”

“Maybe….” Wilde stared at Cerys with growing suspicion. “OK, Chief, I know better than to question, but enough’s enough. Why’s the Legion suddenly interested in F. W. Slater, of all people? I thought he was the socialist we actually liked.”

“‘We’ don’t like any socialists, Max. You know that. They’re dirty, smelly, and untrustworthy, and they usually ask questions ‘we’ can’t comfortably answer.”

“I know the doubletalk, Chief. But honestly, why Slater?”

Cerys sighed, a common precursor to any conversation involving an explanation of orders from the top. “Top brass thinks Slater’s trying to undermine the government with his latest batch of essays. He’s launched another round of anonymous pamphlets demanding improved working conditions, health insurance, abolition of a tax-based electorate, and so on. He’s smart enough to not sign his name, but, like you said, he’s got a distinct voice. We’re pretty sure it’s him.”

“How did he get them past the censor?”

“They were all printed up independently and distributed anonymously: snuck into mailboxes, left on café tables, the usual subversive drill.” Cerys chuckled. “They even had urchins passing them out on street corners. And you know, no one’s as good as those kids at getting away from Legionnaires.”

“Oh, I can just see it!” Wilde laughed, his head filled with visions of brown-uniformed Legion policemen running after hordes of street children.

“Upshot is, we don’t actually know who’s behind it.”

“But top brass thinks it’s Slater.”

“Yes,” Cerys agreed. “But what brass thinks is usually wrong.” She rose from her desk and refilled her cup of coffee, mulling something over. “Max, I’ve got an assignment for you.”

“Whatever you need, Chief,” Wilde answered, eagerly setting aside the pile of pamphlets.

“Don’t sound so excited. I want you to find out who this ‘Salad Monday’ character is. If he’s connected to Slater, so much the better. If he isn’t, at least that’s one little mystery solved.”

Wilde rubbed his head. “Chief, I’ve got to be honest with you: I’m not sure where to start. I mean, he’s been around for ages and no one’s been able to find out who he is. Any lead I can think of has probably been tried already.”

“Has it?” Cerys asked. “Or are you just assuming it has?”

“Point taken.”

“Start with the obvious. He’s got to live somewhere, he’s got to eat somewhere, he’s got to write somewhere. And I may not understand how this titter-tatter thing works—“

“‘Tit-tat,’ Chief.”

“Shut up, Max,” Cerys instructed, before finishing her sentence, “—but somewhere along the line someone has to be getting his comments for print. Find out who, and chances are you’ll find Salad Monday.”

“The printing houses won’t be happy to give up his name and address, you know.”

“Take Kendrick with you. Five minutes with him and they’ll give in.”

“Do I get a warrant?” Wilde asked hopefully.

“I’ll put in a call,” Cerys answered, and took a sip of her coffee. “Until then, improvise.”

“Yes, Chief.”

* * *

Several hours later, Wilde was sipping his own coffee outside a pleasant Layer Three café. It was a trendy sort of place, with the intellectual atmosphere preferred by scholars, students, artists, and anyone who mistakenly believed himself to be one of the above. Wilde leaned back in his wicker chair and smiled as he looked around at the crowds of youths at the nearby tables. They were mostly young men wearing casual sack suits and fedoras, though here and there could be seen young women in shirtwaists and long skirts. A few of these women were bored sweethearts who stared into their cups impatiently or chatted with one another as they waited for their boyfriends to take notice of them. Others were female students determined to do more with their education than find a husband, and were engaged in spirited debate with their male counterparts.

As Wilde’s gaze returned to his own table, it fell upon his dour-faced companion. “Kendrick, don’t you ever smile?”

“Only when I’m shooting terrorists,” came the reply.

Across the table, Kendrick Mernil looked like he had swallowed a radish. Inspector Mernil—of the Special Peacekeepers, as he rarely failed to remind you—was seldom comfortable out of jackboots and armor. To be dressed in the same casual clothes as undisciplined students was galling. Kendrick made a face at Wilde and reached beneath his black suit jacket to check one of his pistols.

“Do you have to do that?” Wilde asked. “You’ll draw attention.”

“When is your damn friend going to show up? We’ve been waiting half an hour.”

“It’s been ten minutes,” Wilde replied.

“And why are we wearing civvies? You know I hate wearing civvies.”

“You hate not having socialists to shoot at. You’d be happy in a barrel if you were firing at something.”

Kendrick struggled to argue with this point, and failed. “Well…I don’t know what good this is going to do anyway. These blasted students have no respect for anyone in authority. Anarchists, the lot of them, if you ask me.”

“Shut up and drink your coffee,” Wilde answered, trying not to laugh. Turning to look back at the street, he spotted the young man they were waiting for. “Ah, here he is!”

The fellow in question was clearly one of the university rabble, and the sight of his mismatched clothes was enough to make Wilde cringe. The young man’s coat was dark green, his vest and baggy trousers brown; yet somehow the colors failed to coordinate. More distressingly, the young man’s tie, while the same green as his coat, was covered in dark spots that were as likely to be ink stains as polka dots. He sauntered across the carriage-filled roadway without a sense of urgency, as tendrils of steam and boiler smoke from the passing vehicles licked at his back and heels. After taking a moment to exchange waves and handshakes with the other students at the café, he dropped cheerfully into a chair across from Wilde. He gave Wilde an affable smile, ordered a cup of coffee from a passing waiter, and then lounged back in his chair with the ease of a man composed entirely of liquid. Then, as if he was just noticing him, the student slowly turned his gaze toward Kendrick—who sat in plain view across from him—and jumped in surprise.

“Hey!” the student hissed at Wilde. “What’s this then? What’s the numb on that one?”

Kendrick looked at Wilde. “The what?”

Wilde shushed him before reassuring the student. “That’s just Kendrick. He’s glass, Manny, he’s glass. He’s OK.”

“I’m what?” Kendrick demanded.

“You’re glass. It means you’re smooth. You’re not…um…bumpy.”

“What?” Kendrick repeated.

“Just shut up and let me do the talking.”

“Hey, now…” Manny was peering very purposefully at Kendrick’s moustache. “He’s a copper, isn’t he?”

Wilde let out a sigh. “Manny, I’m a copper.”

“No, you’re a tatter who cops.” Manny fell silent as the waiter arrived with his coffee. He hid behind the cup, peering over the brim at Kendrick like a small animal watching a dog.

“Manny, I’ll vouch for him: He’s glass, OK? Now, can we move on?”

There was a long silence as Manny continued to peer out over the top of his cup. “OK. Whadya need?”

Wilde sighed. “Will you please put the cup down?”

Manny hesitated for a moment, then looked at Kendrick. “No.”

“Fine.” Wilde sipped his coffee, not in the mood to argue with either of them. “Manny, I need some information from you. You’re the top tatter I know, so if anyone’s got the info I need, it’s you.”

Manny snorted, but he finally relaxed a bit and lowered his cup. “Don’t butter me up, Max; I’m not a sticky key. Just post me the titles.”

“Fine, fine. I need the skinny on Salad Monday.”

“Ha!” Manny laughed. Then he realized that it was not a joke. “You’re not titting me, are you?”

“‘Titting?’” Kendrick interjected, sour-faced.

Wilde turned to him in irritation. “Yes. It’s…. Well, it means you’re playing a joke on someone. Pulling their leg, but obnoxiously.”

“Being a tit,” Manny added, helpfully.

Kendrick’s unpleasant expression darkened further. “A ‘tit?’”

“Yes,” Wilde answered. “It’s a tatter who—“

“I know what a ‘tit’ is, Max, though the tooters sound a bit confused. Probably never seen a real one in their lives.”

Manny made the mistake of trying to be helpful again. “Actually, it’s ‘tatters’—“

Kendrick growled and almost launched himself across the table at the young man.

“Down, Kendrick,” Wilde ordered, mimicking the sharp tone of voice Cerys often used when dealing with Special Peacekeepers.

“Uh…eheh….” Kendrick caught himself leaning across the table and gave an awkward smile. “Right, right…. Sorry. Got, uh, carried away.”

“Yes, well, save that for someone who deserves it.” Wilde drained his cup and set it down. “Look, Manny, I need to find Salad Monday, and I need to find him by this morning’s edition, read me?”

Manny was hiding behind his cup again. “Sharp and fresh, Max, sharp and fresh. But cite the facts: Salad Monday’s been tatting since tatting first hit paper, and no one’s cracked him yet. Eye-moth, cracking Salad Monday’s potsy.”

Kendrick’s eye twitched as he tried to follow the conversation. “What was that?”

“In his opinion, finding Salad Monday’s true identity is like putting one over on the censor. That is to say, impossible.” Wilde turned back to Manny. “But someone out there has to know. Look at it this way: Salad Monday comments on all the big tatting papers. That means he reads all the big tatting papers. We both know you can’t just pick up a broadsheet on the street corner…not yet, at least.”

“Glass,” Manny agreed. “You get the sheets posted special.”

“That means someone’s delivering them to him, and if no one’s cracked him yet, it’s because there’s a reliable middleman. So, Manny, I want you to tell me who that middleman is.”

Manny hesitated for a moment. “What’s in it for me?” Across the table, Kendrick snarled, but Manny pushed on. “Max, you know I can’t go posting you people’s private letters. What kind of a tag would I buy myself with that? Giving out private numbs to coppers, Max…I’d be for the furnace if I did that.”

Wilde sighed. “Manny, you know me. You know I wouldn’t tell anyone where I got my info. And I’ll tell you what, you point me in the right direction and I’ll take you with me to the Martyrs next week. August Mars is playing, and I think I can get you backstage.”

Manny gave Wilde a wide-eyed stare over the top of his coffee cup. “You’d do that?”

“Of course, Manny. We’re friends.” Wilde smiled sincerely, and then turned the screws. “But if we’re going to go, I need to be done with this case, and I can’t finish the case without your help.”

Manny made a face. “You’re turning the cop on me, Max.”

“Manny, you know I’d never do that. But I have a job to do, and I need your help doing it. Just point me the right way. I swear I won’t so much as think your name for the rest of the investigation.”

There was a long silence as Manny stared into his cup. Once or twice he glanced toward the other students, clearly expecting the worst; but as was often the case with young university types, Manny’s friends were too busy talking amongst themselves to realize that he was having another conversation nearby, let alone with whom.

“OK. If you want Salad Monday’s house, you’ll be looking at the tops. Big type printers who won’t be buttered into selling his number, else he’d be cracked already. I only know three: Maynard and Sons; Edgewood, Franklin, and Co.; and Belle Street Printers, Ltd. If they’re not posting for him, I don’t know who is. Read me?”

“Sharp and fresh, Manny,” Wilde answered. “Which one’s the biggest?”

“Belle Street, but I wouldn’t start there.”

“No?”

Manny shook his head and looked around cautiously. “Edgewood’s the only one of the three that printed tit-tat when it first came out. If Salad Monday’s tatting for one of the other two, then he jumped ship from another house a few years back. And when you change houses in tit-tat—”

“The old printers have no incentive to keep your real name a secret,” Wilde finished. “They’d have sold Salad Monday’s identity to the highest bidder by now. Manny, you’re the best. For this, I’ll get you that backstage meeting with Mars.”

“Thanks, Max, you’re OK. Now, uh….” Manny glanced over at the cluster of other students.

Wilde waved him away. “Off you go, Manny.”

Manny grinned awkwardly, still eyeing Kendrick as if the latter were some sort of rabid animal. Then he drained his cooling coffee in one gulp and wandered off to join his fellow students, who greeted Manny with cheers and handshakes as if he had only just arrived. The realization that he had been engaged in conversation only a few tables away was completely lost on them.

“Right,” Wilde said, throwing down some money and rising from his chair. “Off we go, Kendrick. Time to put the fear of Heaven into some people.”

“Now you’re using words I understand,” Kendrick replied with a terrible smile.

* * *

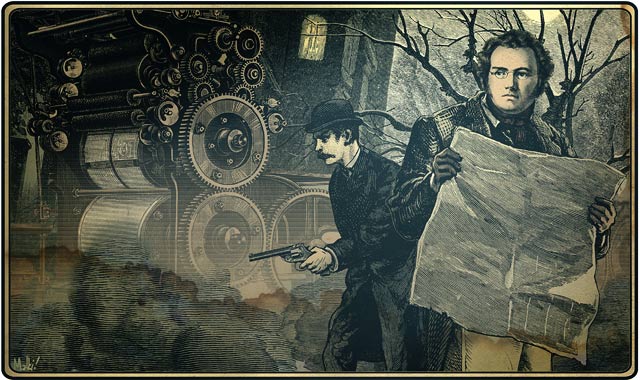

The printing house of Edgewood, Franklin, and Co. was perhaps the noisiest place Wilde had ever been. From the vantage point of a second-story balcony, he watched two rows of automated printing presses rapidly turning cylinders of pulp paper into piles of broadsheets. In between, engineers in oily clothes scurried back and forth, anticipating breakdowns and lubricating the countless moving parts. Junior clerks rushed from machine to machine, retrieving armloads of printed papers and resetting type codes. Off in rooms to either side, typists could be seen at their desks, using complicated keyboards to set the type codes for the next batch of issues.

Of course, Wilde recalled, his second-story position was an illusion. In fact, he was six floors above the street, since the room he was in rested on two identical chambers filled with printing presses and typesetters. Like many of the businesses in the City of Salmagundi, Edgewood, Franklin, and Co. had maximized their efficiency by capitalizing on vertical space. Indeed, the printing house tower continued further upward with several floors of offices above the printing halls.

“Now then, gentlemen,” said the upright and stern-faced Mr. Edgewood, “I expect we shall enjoy a little more privacy here than in my office. What is this ‘delicate matter’ you feel you must discuss with me? At the outset, I should like to remind you that we take no responsibility for the content of articles printed by our company. If you’ve been offended by something, you must take it up with the author.”

“No, no, nothing of the sort,” Wilde assured him, “but we are interested in contacting one of your authors.”

“Oh, yes?” Edgewood said, his tone not altogether pleasant.

“I understand you’re the printing house that works with the commentator known as Mr. Salad Monday. Is that correct?” It was a bluff, of course, but worth a try.

Edgewood studied the two men before him in silence. At length, he answered, “Very well. I don’t know how you found out, but yes, he is one of our clients.”

“Then I assume that your company arranges to have his papers delivered as well.”

“Yes…” came the cautious reply.

Wilde smiled. “In that case, sir, I need to know who he is…or at least where he can be found.”

Edgewood’s face paled horribly, then flushed with great offense. “You expect me to give out the private address of one of our clients?”

“Yes,” Wilde answered flatly. “I assure you, Mr. Edgewood, that we’ll keep your involvement strictly confidential, but I need that information.”

“Inspector, you don’t seem to understand, so let me make this exceedingly clear to you. The anonymity of my clients is a sacred trust, as surely as if it were sworn in the presence of a priest or a magistrate. The credibility of this printing house demands that we bow to neither bribery nor intimidation, and I am not inclined to make an exception for the likes of you.” He brushed at the lapels of his frock coat dismissively. “And don’t try to threaten me with that policeman’s nonsense of yours either. I know my rights as a taxpayer. I’m above your routine harassment. You don’t even have a warrant, or else you’d have shown it to me by now.”

“Mr. Edgewood, I think you’re being somewhat unreasonable here. I’m asking for the address of one man.”

“Principles, Inspector.”

Wilde tried a different approach. Narrowing his eyes, he moved half a step closer to Edgewood than most people would have found comfortable. “I arrived without a warrant out of consideration for your reputation, Mr. Edgewood. You aren’t a suspect here, so why bother with all the ribbon?” He assumed that Edgewood, like most citizens, could be brought into line by the threat of red tape.

Edgewood was unmoved. “They wouldn’t give you one if you tried, Inspector. I am a taxpayer, if you recall. Go and try your strong-arm methods with those paupers down on Layer Five. I have no time for it. I expect you two can see yourselves out. Don’t soil anything on your way to the door.”

He turned to walk away, fingers tucked around the edges of his vest, but instead of the open walkway, he found himself confronted with Kendrick’s bowler, dark suit, and quivering moustache. Without a word, Kendrick gripped Edgewood by the lapels of his coat and lifted the smaller man into the air.

“I say, how dare—“ Edgewood began.

“Let’s try it this way,” Kendrick interrupted. “I’m going to count to ten. If you’ve answered the Inspector’s question by then, I’ll put you down. If you haven’t, I’ll count to ten again. If you answer by then, I’ll put you down on the printing room floor,” he said, nodding to the open chamber that lay a dozen feet below them. “But if you still haven’t answered, I’ll put you down outside the window. And we’re…” he turned his head to Wilde, “what, fifty feet up?”

“More like seventy,” came the deadpan reply.

“But…but….” Edgewood was struggling to understand that a policeman had dared to manhandle him. “You can’t do this!”

“One,” Kendrick counted.

“I think you’d better do as he says,” Wilde offered, with a helpless shrug.

“Two.”

“But I’m a taxpayer!”

“Three.”

“You’re peacekeepers! You can’t do this!”

“Four.”

Wilde shook his head. “No, I’m a peacekeeper.”

“Five.”

“He’s a ‘special’ peacekeeper.”

“Six.”

“Special?” Edgewood gasped, all the more frightened that he did not understand the significance.

“Seven,” Kendrick said, exchanging nods with Wilde.

“Special,” Wilde confirmed.

“Eight.”

The color drained from Edgewood’s face, and his head snapped toward Kendrick as he struggled to say something, anything, to halt the counting.

Kendrick gave the man a sympathetic smile.

“Nine.”

* * *

The address belonging to the mysterious Mr. Salad Monday was a small townhouse located in of one of Layer Three’s poorer neighborhoods. While hardly approaching the squalor and poverty found among the laboring classes of the lower city, the less affluent residents of the bourgeois Layer Three still lived in an unenviable state. Their houses were often old or run-down, and it would be dubious to claim that they were truly worth the rents they paid. But surely, the landlords insisted, the superior ambiance of the layer was more than compensation for the extra cost.

Salad Monday’s townhouse was a weathered brick construction, similar to many of the neighboring buildings. It rested at the end of a long alleyway, one kept clean as much through the locals’ efforts as the municipal workers’. It seemed doubtful that the city sweeping machines could even fit down the narrow street.

The front door was locked, of course, but it was a poor Legion officer who was not a good housebreaker. The building’s interior was solid but weathered, with peeling, yellowed wallpaper that no one had bothered to replace in ages. Thick sheets of dust covered everything, confirming the building’s general disuse, and there were no footprints or signs of passage to be found upon the floor, stairs, or banisters.

In the ancient foyer, Wilde glanced at Kendrick, only to see that the other man had drawn two service revolvers from inside his coat and was peering along them toward the interior of the house.

“Kendrick!”

“What?”

Wilde made a face as he led the way into the front hallway. “Put those things away.”

Kendrick’s eyes darted around the hallway, peering at the dim gaslamps and dusty surfaces as if they might attack at any moment. “There could be terrorists.”

“Terrorists who don’t leave footprints? Be sensible. Besides, if there is anyone here—which I’m beginning to doubt—it’ll be a lot of idiot students, not armed men.” Some distant sound caught his attention. He held up a hand for silence, ignoring the fact that he was the one speaking. “Shhh. Do you hear that?”

The two men listened for a moment. Presently they heard a noise rising up through the hallways of the house. It was the all-too-familiar sound of perhaps a dozen typewriters clacking away in unison. The clicks came from further in the house, slowly trickling along the layers of dust until it seemed they emanated from the very walls. The two officers looked about, turning this way and that as they strained to hear where the sound could be coming from.

“Well, there’s clearly someone here,” Wilde noted softly.

“Must be using a back entrance to avoid footprints,” Kendrick agreed. He raised his pistols and began to edge along the corridor. “Bastards are probably downstairs in the cellar.”

Wilde tilted his head. “Wait, Kendrick. I think it’s coming from upstairs.”

“Then search up there if you want,” Kendrick answered, peering around a nearby corner as if he expected hordes of terrorists to be lying in wait. “I say it’s the cellar, and that’s where I’m going.”

Wilde knew better than to argue. As Kendrick disappeared in search of the cellar door, Wilde made for the stairway. The sound of typing was clearer on the second floor, and clearer still as Wilde climbed upward toward the third. The rooms on this floor bore the only signs of habitation; for though there was no activity, they were filled to bursting with piles and piles of newspapers, broadsheets, chapbooks, and other printed materials. The heaps of paper had been neatly placed in some sort of complex order, but nothing had been done to protect them from moths and insects. Many of the papers had been partly devoured by whatever loathsome vermin infested the house.

He exited the room. Dust was everywhere, as thickly layered as on the first floor, but in the hallway Wilde noticed some curious trails upon the ground. Here and there the dust had been disturbed in narrow, twisting lines. Wilde knelt to study these, but he could make nothing of them. They clearly led up and down the stairs in the direction of the front door, but what they were or what they signified remained unknown. If anything, it seemed like someone had trailed the tips of feathers through the dust.

The stairs continued upward to a single attic door. Just upon the threshold, the typewriter clacking was incredibly loud. Wilde felt a shiver descend along his back. There was no reason for fear—the typists were, no doubt, only foolish students who would be as likely to run or beg mercy as fight—but Wilde’s instinct for danger was still working full-time. Reaching for the handle, Wilde eased the door open and stepped into the room beyond. He did not immediately understand what it was that he saw.

The room was larger than it appeared from outside, for it stretched almost the full length and breadth of the house. The peaked ceiling was exceedingly high, and from it hung a series of burning lamps that kept the attic space bright enough for typing. Piles of printed broadsheets littered the floor. A number of tables had been placed about the center of the room in a rough circular shape, and they were covered variously by stacks of blank paper, typing ribbon, and easily a dozen typewriters. There were no chairs in front of the tables, a point which at first confused Wilde. He was likewise bewildered by the room’s clear desolation: there was no one to be seen anywhere. And yet the typewriters were clicking away still, as if driven by the hands of ghosts. At first, Wilde thought the machines might be automated, but he could see no punchcard reader to direct them, nor steam lines to power them.

As Wilde approached the typewriters, he became aware of certain peculiar details that he had not initially noticed. It seemed as if a series of silken streamers had been hung from the ceiling over each keyboard, yet if the tendrils were cloth or thread, they must have been waxed to give them that unthinkable glisten. There was a luster to them, yet at the same time they were all but translucent. They seemed more mirage than substance and were a curious iridescent color, an impossible mixture of blue, violet, turquoise and magenta. The tendrils all seemed to drift and float through one another like trailing strings of light, yet they were somehow responsible for the movement of the typewriter keys.

Wilde’s eyes followed the fantastically colored lines upward toward the peak of the roof, where they joined together into a layered mass of themselves. This “body,” if such a term could be applied to it, was something akin to a pile of translucent gelatin, with lines and layers too numerous for the eye to understand. In some parts of the floating mass there were strange concentrations of light. These, Wilde suddenly realized, were eyes. Each was fixed diligently upon the typewriter below it, though they were all clearly working independently of one another. As Wilde watched, a collection of tendrils paused in their typing and reached out to a pile of broadsheets. The paper drifted toward the underside of the floating mass, and the folds of the vibrantly colored dome pulled back to reveal a series of things that might have been mouths, or mandibles, or complex beaks. These began to devour the printed newspaper hungrily.

Wilde stood rooted to the spot, gazing in fear and rapture at the floating thing. He was too good a policeman to simply dismiss the sight outright, but his mind worked double-time to find some comfortable explanation that could make sense of the combination of place, time, and creature. It was tempting to think that the creature’s presence might be some terrible coincidence—that it had happened along and eaten the house’s occupant moments before Wilde’s arrival—but the most impossible answer was also the simplest: The floating mass of tentacles and iridescence must be Mr. Salad Monday.

As he stood and watched the creature devour its meal of decaying broadsheets, Wilde’s first realization was followed by another. It was all to do with paper. The heaps and piles of paper scattered throughout the house were not simply pieces of a decaying archive. They were both food and entertainment. There was little doubt that Salad Monday the tatter enjoyed the challenge of typewritten argument, but it seemed that Salad Monday the monster also enjoyed the pages upon which the arguments were delivered.

In spite of himself, Wilde coughed. One cluster of lights rolled through the curious mass to fix its gaze upon the intruder. These stared at Wilde for a moment, twitching monstrously as they tried to bring him into focus. Then another set joined them, then another. Soon it seemed that all of the dreadful eyes had migrated to one section of the body and were staring at the solitary figure below. The dangling tendrils ceased their typing, and the room fell silent. Wilde licked his lips and realized that he could not seem to raise his pistol. He stared at the creature’s eyes and saw in them what might have been hunger or malice or fear.

Then, without a moment’s warning, Salad Monday’s tendrils quivered and tucked themselves up beneath the folds of its floating body. The mass of color rippled violently, and suddenly it was gone, vanishing upward into the dark rafters. As Wilde stared, he thought he could see hints of movement pass through the blackness above the lamps and toward the far end of the attic.

A moment later the door burst open behind Wilde, and Kendrick rushed in with his revolvers raised. “You’re right, Wilde!” he cried. “Cellar’s emp—“ Kendrick paused for a moment as he saw the array of now-vacant typewriters. “Bastards!” he cried. “Don’t worry, Wilde, we’ll find the buggers. They can’t have gone far.” And with that, Kendrick bolted across the room and into a back hallway, ignoring completely the floor’s lack of footprints or signs of human passage.

“Kendrick, wait!” Wilde shouted. His words fell on disinterested ears. Kendrick’s blood was up, and he was too hot on the chase to bother with details such as who he was chasing or where they had gone.

Kendrick searched around in the mouldering dimness of the attic for a few minutes, overturning piles of paper and kicking at bits of rubbish that lay long abandoned upon the floor. Finding no students or terrorists hiding in the shadows, he flung open an exterior door on the other side of the attic and dashed outside.

“They’ve gone for the rooftops, Wilde!” he shouted. “C’mon, we’ll catch them in no time!”

Wilde watched in silence as Kendrick dashed off on his mad chase. Shaking his head, he began to walk toward the outside door, thinking that he ought to catch Kendrick up before the other inspector ran too far afield.

A strange rush above his head drove Wilde to glance upward, and he caught a glimpse of luminescence pass along the spine of the ceiling. Turning, he saw the strange lines and colors of Salad Monday hovering above the circle of typewriters. The creature had given the illusion of departure, then sought to backtrack toward the stairs.

“Cunning devil…” Wilde murmured.

Salad Monday’s tentacles extended downward in clusters and began to wrap around a couple of the typewriters. Wilde watched in confusion, uncertain what was being done. The typewriters were slowly raised into the air, held beneath Salad Monday’s quivering multi-colored mass with the care of a mother cradling a child.

Not sure what to do, Wilde extended a hand and called out to the floating shape. “Stop!”

Salad Monday shook in surprise, and its bright eyes darted through its body and clustered on the side that faced Wilde. The creature began to edge back toward the staircase, behaving less like a ravening monster and more like a frightened animal.

“Stop!” Wilde repeated, slowly advancing to match Salad Monday’s pace. “Can you understand me?”

Salad Monday shivered slightly, but there was some sense of comprehension in the brightness of its eyes.

“I’m from the Legion of Peace,” Wilde continued, keeping his voice level. “Do you understand?” He motioned to himself. “Police.” He took a few more careful steps forward. “I know who you are. You’re Mr. Salad Monday, aren’t you?”

Wilde had hoped this pronouncement would help to set Salad Monday at ease, by acknowledging the creature as something with an identity rather than some unthinking monster. Instead, as the name was uttered, Salad Monday drew itself up, eyes shining with the same terror that it had shown when Wilde first arrived. With barely a moment’s hesitation, Salad Monday rippled like a sheet in the wind and dove down the stairs with tremendous speed.

“Oh, Hell!” Wilde swore, dashing after the receding shape.

He scrambled down the dusty stairs to the third floor, head turning this way and that as he tried to keep sight of Salad Monday. He caught a glimpse of the creature on the way to the second floor, but it was a fleeting one. Continuing downward, Wilde’s feet struck a smooth patch on one of the steps and he lost his balance. His head struck the wooden boards with a painful smack, and he lay in a daze for a moment.

Shaking his head, Wilde pulled himself to his feet and rushed down into the front hall, determined to make up for lost time, but at the bottom of the stairs, he was met with silence. Cursing softly, Wilde rushed through the deserted rooms of the crumbling house and the alleys outside, searching in desperation for the creature that he had come to find. He was met with desolation. Mr. Salad Monday had vanished, seemingly into the very woodwork itself.

* * *

Wilde finally returned to the Chief Inspector’s office at the end of the day, still in a daze. He and Kendrick had searched every inch of the house—first on their own, and later with a squad of Legion soldiers from the local precinct house—but it had been of no use. They had confiscated the remaining typewriters, along with boxes of replacement keys and ribbon. There had been a limited attempt to catalogue the piles of broadsheets and books, but that had quickly been abandoned as an act of futility.

Wilde found Cerys behind her desk, glaring at a mass of paperwork that seemed to have grown rather than diminished since Wilde’s departure. Wilde entered and softly closed the door. Cerys was busy selecting a cigarette from a battered tin case, and she did not look up as she motioned for Wilde to join her. The air was already thick with smoke and fragrances of half a dozen different blends; it went without saying that the ashtray was overflowing.

“Lavender?” Wilde asked, noting the smell of the smoking herbs. He set a bundle of fresh evening broadsheets down on the chair next to him. He had bought them before dinner, but in his agitation he had been unable to read them.

“I’m celebrating my funeral early,” Cerys replied. “What’s the word on Salad Monday? Is he a terrorist?”

“Chief, you won’t believe what happened.”

Cerys—who had her nose buried in a bundle of forms—looked up at him and took on one of her very particular expressions. “Max, stop. Don’t tell me. I don’t want to know.”

“Chief?”

Cerys took out her pocket fire and lit a fresh cigarette, releasing a cloud of lavender-scented smoke. “I know that look on your face, and it tells me I sure as taxes don’t want to know what just happened to you. All I want…no, all I need to know is whether Salad Monday is going to be a problem. Is he a terrorist?”

“Um…no.”

Cerys flicked her pocket fire on and off as she continued her questioning. “Is he working for Slater?”

“No.”

“Is he a threat to the city?”

“Well, I don’t think so. But, Chief, he’s not even—“

Cerys pointed a handful of papers at Wilde in a most menacing fashion. “Max, I’ve done this job long enough to know that when someone comes to me and says ‘Chief, you’ll never believe what I saw,’ they’re either lying or telling the truth. Either way, I don’t want to know unnecessary details that will one day drive me to drink.”

“You already drink.”

“I’m just getting into the swing of it,” Cerys replied. Then she gave him a sympathetic look. “Max, I’ve seen my share of unbelievable things in this blasted city. Take my advice: don’t think about it too hard. It’ll hurt less that way.”

Wilde slowly unrolled one of the broadsheets and tried to relax. “It’s that easy, is it?”

“Drinking helps.”

“Mmm.”

Wilde was doubtful about his ability to put such an experience out of his mind, so he turned to the best source of distraction he could think of. The pointless arguments and self-important tirades of the tit-tat broadsheets began to soothe his shaken nerves, and soon Wilde was on his way to easing the strain of his recent discovery. Then he turned to a second printed page. His eye caught a name that was new, but unmistakably familiar.

“Ahh!” he cried, leaping from his chair.

Cerys looked up from her paperwork again, flicking her pocket fire on and off in nervous habit. “What?”

Wilde thrust the broadsheet toward Cerys and pointed at a small section of print located just beneath the main articles. It read very clearly: “Though circumstance demands brevity, let me say simply that Mr. Jervais Mutton is, as ever, a dunce hardly worthy of consideration. Anyone doubting this fact should turn to his latest comment regarding the need for a citizen militia to protect us against the danger of unwed mothers. Additionally, while the police provide a useful service to society, their violation of the homes of private citizens does not do their reputations credit. Discuss. Yours sincerely, Mr. Herring Tuesday.”

“It’s him!” Wilde cried. “It has to be him! He can’t have written this more than an hour after I found him…it…him…. It’s still out there!” Wilde tried desperately to convey to his superior the gravity of the situation. The result was less than profound. “Tentacles, Chief!”

Cerys was very familiar with the look on Wilde’s face. She had seen it on her own reflection in the mirror more times than she could count. It was the look of someone who had witnessed the unthinkable and was trying desperately to make sense of it.

“That’s it, Max, early night for you. Go tell Marguerite you’re taking her to the cinema.”

“But—“ Wilde protested, pointing to the broadsheet.

“Out!” Cerys glanced at her chronometer, then rummaged around for an amusements circular on her desk. “If you two can catch an omnibus in the next ten minutes, you’ll be at the Palace in time for the newsreel and cartoon. And look at that…tonight they’ve got another adventure of Minnie the Mouser. Won’t that be fun?”

“Chief—” Wilde tried again.

Cerys glanced at her chronometer again. “Nine minutes.”

Wilde sighed. “OK, Chief, OK.”

“There’s a good fellow.” Cerys pushed the young man toward the door. “Go have fun. Oh, and Max….”

“Yes, Chief?”

Cerys gave Wilde’s shoulders a purposeful squeeze. “If you get her into trouble, I’ll kill you.”

“Oh, come on, Chief, it’s me!”

“That’s the idea.”

When Wilde had gone, Cerys returned to her desk. She stared for a long while at the mountains of paperwork, her eyes slowly and consistently drifting back to the stack of broadsheets Wilde had left. Then, with a sudden rush of purpose—or perhaps procrastination—she snatched up a pen and began to compose a letter. She addressed it to the printing house responsible for the comment by “Mr. Tuesday” and then began writing, in the most grandiose language she could imagine. “To Messrs. Monday and Tuesday, with assorted foodstuffs. Dear sirs, our humblest apologies for intrusions, etc. Necessities of the work, etc. In future, please refrain from frightening respectable policemen in pursuit of their duty, etc. Humbly, etc., the lady on the Broad Street omnibus, Mrs.”

Chuckling to herself, Cerys set the note aside, intending to dispatch it when she left for the night. There was no telling whether it would ever been seen by Salad Monday, but at least the thought of it amused her.

A nagging thought tugged at the fringes of her imagination, and for a moment Cerys found herself contemplating the implications of what Wilde might have seen.

Tentacles.

Clearing her throat to dismiss such thoughts, Cerys lit another lavender cigarette and spent a few moments staring into the flame of her pocket fire. Then, with a familiar sigh, she turned back to the mountain of paperwork on her desk. She was tempted to set fire to the whole lot, and she smiled wistfully at the thought. She was still smiling, with visions of bureaucratic conflagrations in her head, as she turned to the next case file in her unending pile of assignments.

Copyright 2009 © G. D. Falksen

“So ‘IIMOT’ means…?”

“We pronounce that ‘eye-moth.’ It means ‘it is my opinion that.’

“What about ‘IHN?'”

“‘In Heaven’s name,’ Chief.”

Oh, no–it’s USENET on broadsheet!

I love it.

Glad to read more from GD FALKSEN. I loved the serial “The Strange Case of the All Seeing Ear” in The Willows magazine. Salmagundi is a wonderful creation.

GD Falksen has a truly unique imagination. Love it!

I really really liked this. It’s like there’s an implied critique of the characters for thinking they’re more important than they really are — but at the same time, when Wilde needs to relax, Cerys just pushes him to an even more trivial and mindless form of entertainment. Still, well told.

Ethan

that was one hell of a story. very original and well written. I loved it. Ah, how different our world would be if we didn’t have our tit-tats. I’ve seen so many Mr. salad monday on infinite number of forums.

What a wonderful ride! I hope this is a serial to return soon or a more regular feature here. Consider me a new fan!

I liked it! Very cute story and a nicely envisioned world.

Wonderful story. The carry-over of pronounced abbreviations/acronyms threw me off for a minute, but then I settled down and realized it was a perfectly reasonable habit for the tatters to fall into. Wilde also seemed a bit schizophrenic, being so prone to laughter in the first half, then exhibiting a harder edge during the confrontations, and finally giving in rather easily to Cerys’s suggestion to let it all go. I still enjoyed the story immensely. This is my first time to this site and I hope to see more of Falksen’s work here!

Really good story!

Geoff

What I would love to know is, dose Mr Monday look how an Octopus would look where it a jelly fish or is it how a jelly fish would look where it a Octopus?

Please, Tor, please stop dividing stories into multiple pages! or at least provide a ‘view all’ option.

I always download anything longer than about 300 words as too much screen time plays havoc with my health (eyes -> migraine -> sometimes several days before i can use a computer again, so it’s *really* worth the trouble of copy + paste). I’m sure i can’t be the only person to whom it makes a big difference, for many reasons.

I’ll try n remember to come back n comment after i’ve read this. First impressions are good. :0)

Some of the better fiction I’ve read lately has come from TOR.COM.

I really enjoyed this story, and the world/city of Salmagundi – I’d love to explore it further.

The Naked Brains of Zeppelin City, now Mr Salad Moday… what is it with the blobby shapeless sentient creatures thing?

=)

A very good story. I’m a scholar myself (same age as Falksen, too) and I loved the way he built the narrative on historical features: the broadsheets, the printing houses, the different social classes…

@11: what about downloading the pdf? That’s what I always do, although I end up reading these stories on my pc screen anyway.

Lol…Good yarn, with enough ends left dangling to warrant a continuation. (puns intended) Very enjoyable and well-imagined. It’s a world that I would certainly like to explore further.

Great story!

Excellent story, thank you! Very engrossing but not long enough :) I got here through wondermark.com lets hear it for steampunk.

Messrs. Falksen and Malki in the same place? This is a good thing to see.

A nicely told steampunk story. Mr. Salad Monday seems like an adequate doppelganger for the Flying Spaghetti Monster. My thanks to Mr. Malki! (to use his idiosyncratic formulation of his name) for directing my attention thisward.

Great story, I liked it! Very cute and a nicely.

Delightful story. Well written and exciting to read. Great characters.

If only his stories were as interesting as he is.

Sorry, but I find his work a good cure for insomnia.